Visitors / Employees

Why Some Parklets Work Better Than Others

Originally published at The Atlantic's Citylab blog

The concept of the Parklet—the conversion of a couple of curbside parking spots or other underused public space into a tiny park, complete with greenery and seating—got its start in San Francisco about 10 years ago. Since then, the idea has decidedly spread, in part through temporary “Park(ing) Day” events, but also through more permanent efforts that have sprung up across the country, everywhere from Seattle to New York, Los Angeles to Minneapolis, even suburban New Jersey.

These urban innovations are not without their detractors or problems. One parklet, in San Francisco’s Castro District, has proven to be a center of controversy thanks to nuisance activities (booze) and a small handful of unusual users (nudists). Another, in Boston, was eliminated because of adisagreement between two neighboring business owners: one liked the parklet, the other wanted the parking places given back to cars. But these are the outliers. In general, parklets have been well-received in communities all over the U.S.

"One business owner said sales were up so much he had to hire new workers."

But what exactly does a parklet achieve? For instance, how many people really use them? The folks at University City District, a nonprofit neighborhood development organization in Philadelphia, wanted to find out. UCD worked with the city to install Philadelphia’s first parklets in 2011, and currently operates several each season in partnership with local businesses. Now the group has released a report that analyzes detailed observations of six Philadelphia parklets during the 2013 season. UCD hopes to use the data to increase the positive impact such projects have on the community.

“We heard a lot of anecdotal reports about the parklets,” says Seth Budick, policy and research manager at UCD. “One business owner said sales were up so much he had to hire new workers. What better economic development could you hope for than that?”

One of six Philadelphia parklets studied by University City District. (Ryan Collerd/UCD)

Anecdotes, however, weren’t enough. Budick says the report aims to nail down a more sophisticated understanding of what works and what doesn’t in the realm of parklets. And while studies in New York, Los Angeles and Chicagohave looked at parklets in central business districts, this is one of the first serious efforts to examine them in a neighborhood setting.

What UCD found is that parklets located directly outside the right types of businesses can create a dynamic that brings a neighborhood together—picture families stopping for dinner or treats, lingering to socialize, and attracting passing acquaintances to stop and chat. The most successful parklet in the study, a 240-square-foot space located outside a taco shop and a popsicle store in a medium-density residential area, attracted as many as 150 individual users in a single day.

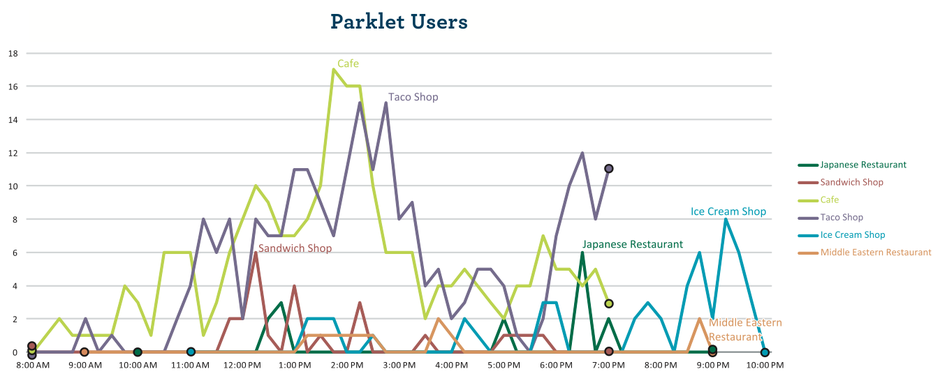

Each parklet's peak use time varied depending on their location. (University City District)

In particular, two parameters emerged as the strongest predictors of parklet success. The first was modest interior seating capacity within a main adjacent business, coupled with high turnover of that same interior seating. The second was large windows on the main adjacent business, which tend to increase the sense of connection between the business interior and the exterior parklet space.

The study also found that the parklets attracted a roughly even mix of men and women, a statistic that would indicate they are safe and welcoming spaces. And 20 to 30 percent of users were not customers of an adjacent businesses, answering concerns that the creation of a parklet removes street space from the public realm for the sole benefit of a private business.

For participating businesses, however, the benefits are clearly measurable. Owners reported a 20 percent increase in sales in the two weeks following a parklet installation, the report notes.

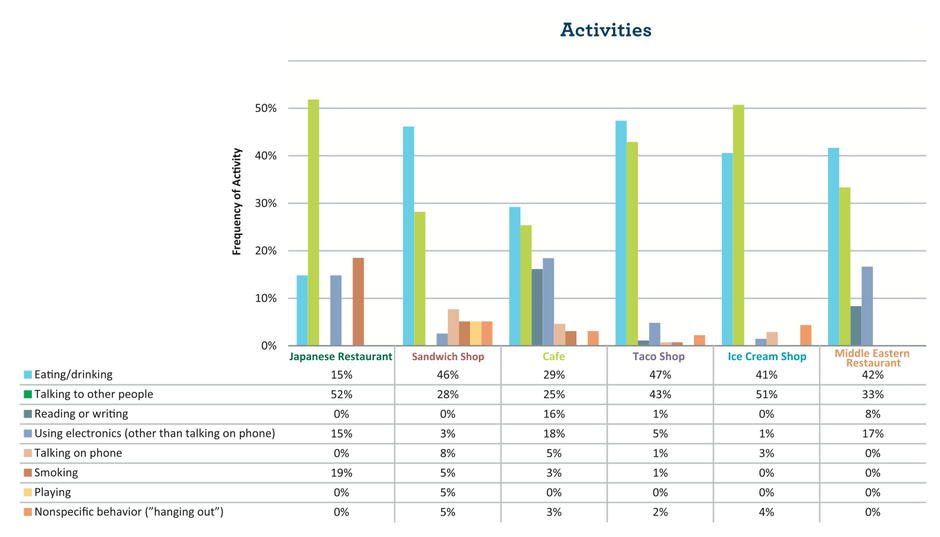

“Put all these things together and something new emerges,” says Budick. “All of a sudden everyone in the neighborhood is stopping there.” Most of the Philly parklets are located outside restaurants, and eating, drinking, and talking with others were the most common activities. In the one example located outside a café, more solitary pursuits such as reading or writing were more popular.

UCD has a history of executing extensive analyses on the success or failure of the public spaces it operates, most notably The Porch, a flexible outdoor seating area adjacent to 30th Street Station that UCD inaugurated in 2011. Prema Gupta, UCD’s director of planning and economic development, thinks this new report will make it easier for UCD, as well as any other organization working to create new parklets, to explain the potential benefits of removing a couple of parking spaces.

“An argument we made very qualitatively before, we can now make quantitatively,” says Gupta. “Are those two parking spaces better used by 150 unique users? Or by two cars?”

BY SARAH GOODYEAR